By James J. Pulizzi

Should we travel to London hoping to pay homage to William Blake’s (1757 – 1827) grave—as we might for Newton, Keats, Wordsworth, or Tennyson—we’ll find a spartan headstone that indicates only his bones lie nearby. Bunhill Fields where Blake was buried in 1827 closed as a cemetery in 1854 when its four acres were already filled with the bodies of over 120,000 dissenters and nonconformists. Nazi bombing during the Blitz severely damaged the northern area of the cemetery, so the City of London Corporation decided to clear the area and create a community garden. Blake’s remains lay somewhere on that now echoing green just north of the City of London near City Road and the A5201 along with those of John Bunyan, Daniel Defoe, and others who dared not submit to the Church of England’s ecclesiastical authority. As the institution that crowned the kings and queens of England, to refuse to conform was in the eyes of many of the powerful to foment treason against the monarchy—James I of England after all had remarked, “No bishop, no king”.

Blake would hardly have been troubled by the absence of bishops or kings, for even though we canonize him today as a great poet and artist alongside Milton, Shakespeare, Keats, Shelley, and others, he denied that any one institution could instruct and enslave humans in doctrines purporting to be spread the ultimate word on faith, truth, and love. Despite living an insular life in London—a city he left only once for a few months—as a printer and artisan always wanting for money, Blake followed his peculiar vision regardless of what orthodoxies the path might lead him to trample. He was an antinomian who took inspiration from the revolutions in America and France against the old, stale order in favor of the spirit of liberty. He supported the rights of women and opposed slavery. He espoused a doctrine of sexual liberty that would have even permitted multiple partners in marriage (a stance he could never convince his wife to accept, however). The Law, or Nomos (νόμος), attempted to impose stasis on the organic and evolving sphere of human activity and thought. Established religions, like their temporal twins in government, preached hypocrisy, cruelty, and preferred humans to repress their urges or energies, as Blake called them, for the sake of maintaining order.

There was nothing illegal, for instance, in the young chimney sweeper being sold into the trade before his “tongue / Could scarcely cry ‘weep! ‘weep! ‘weep! ‘weep!” (The Songs of Innocence ). It is not a bishop or vicar who gives the wee chimney sweep hope for liberation—that comes only in a dream or vision at night:

And so he was quiet; and that very night,

As Tom was a-sleeping, he had such a sight, –

That thousands of sweepers, Dick, Joe, Ned, and Jack,

Were all of them locked up in coffins of black.

And by came an angel who had a bright key,

And he opened the coffins and set them all free;

Then down a green plain leaping, laughing, they run,

And wash in a river, and shine in the sun. (Erdman, 10)

The light of day promises not revelation but only climbing through the despoiling soot of middle and upper class fireplaces. True sight comes only with the night, as the rhyme not subtly implies, when the simple rhyming couplets pick up pace and free the children from their waking dread.

However, the vision is not complete with this dreamed escape, because the Songs of Experience will reprise the “Chimney Sweep” and remind us of the circumstances that led to these children toiling as slaves:

A little black thing among the snow,

Crying “‘weep! ‘weep!” in notes of woe!

“Where are thy father and mother? Say!”–

“They are both gone up to the church to pray.

“Because I was happy upon the heath,

And smiled among the winter’s snow,

They clothed me in the clothes of death,

And taught me to sing the notes of woe.

“And because I am happy and dance and sing,

They think they have done me no injury,

And are gone to praise God and his priest and king,

Who make up a heaven of our misery.” (Erdman, [page])

The aabb rhyme scheme of the Songs of Innocence version reappears in the first stanza but quickly gives way to the alternate rhymes caca dede of the stanzas that turn not inward to the chimney sweeper’s imaginative escape but to the complicity of trusted authorities—parents, the church, and the law—in the child’s plight. The good Christians who sing in church and who feed and clothe poor chimney sweeps by giving them honest work can feel content with themselves as they sing during a Sunday mass, because they have done their part to keep the world running and everything in its place.

Despite his heretical (from his contemporaries’ perspective) proclamations, Blake was intensely religious; he participated in no revolutions (except, perhaps, for the Gordon riots); married just one woman; and composed highly structured, lyric poems intertwined in finely delineated prints whose technique bore closer resemblance to the geometry of classical painting than to the brooding, pulsing art of the Romantics among whom scholars often classify Blake. Yet, the contradictions, or “contraries” as he calls them in his works, would not have troubled him, because they underlay the complex symbolism and mythology of his artistic works. To be alive and human meant to be trapped between opposing forces, and the dynamism provided the movement necessary for life—stasis is death. As he wrote in the “Proverbs of Hell”:

The cistern contains: the fountain overflows

One thought, fills immensity

Always be ready to speak your mind, and a baseman will avoid you. (Plate 8, Erdman, 36)

Expect poison from standing water. (Plate 9, Erdman, 37)

The cistern may contain the water within it and hold there completely, but it cannot contain all water, only a stale remnant of the whole. The fountain is a more productive symbols for Blake since the water issues forth continuously into the surrounding pools before dispersing outward into the world. The fountain’s water never grows stale or disease ridden like so much standing water before the age of municipal sewage and swamp clearing.

Perhaps the evolution of the Bunhill Field would have tracked Blake’s dialectical and unorthodox thinking as the land where he was interred evolved from its inglorious beginnings as a dumping ground for victims of the plague during the 1665 outbreak, to a cemetery that contained the bodies of those who would have likely condemned one another to hellfire in life, and finally into a garden and memorial for some of the United Kingdom’s most respected artists and thinkers. Or perhaps the official recognition and admiration would have signaled the time for further exploration of ideas less amiable to the current Zeitgeist. Where Blake is concerned, it would always be difficult to speak (or type) with anything approaching certainty.

Living on the fringes of political and cultural life in 17th and 18th century London permitted Blake a freedom he might not have enjoyed had been subject to greater attention and scrutiny by the authorities. For outside a close circle of printers and poets, Blake was not a well-known or necessarily respected name. His singular ideas about religion and open discussion of his visions led even those who did know of him to consider him a crank or a madman who was neither writing nor painting in the vein of the Romantic artists. The diarist Cragg Richardson reports that William Wordsworth, upon reading Blake and hearing about his religious visions, quipped that “There was no doubt that this poor man was mad, but there is something in the madness of this man which interests me more than the sanity of Lord Byron and Walter Scott.”1 Therein lies Blake’s contemporaries’ assessment: a fascinating but crazy man.

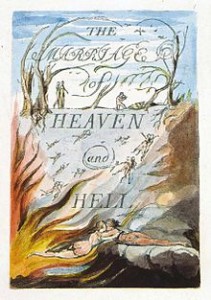

Had they been more widely read, Blake’s poems would not necessarily have enamored the establishment of him, because the contraries in which he espoused his so-called heretical beliefs were difficult to understand. On plate 4 of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell he juxtaposed the following six proclamations written in “The Voice of the Devil”:

All Bibles or sacred codes have been the causes of the following Errors.

1. That Man has two real existing principles Viz: a Body & a Soul.

2. That Energy, called Evil, is alone from the Body, & that Reason, called Good, is alone from the Soul.

3. That God will torment Man in Eternity for following his Energies.

But the following Contraries to these are True

1. Man has no Body distinct from his Soul for that calld Body is a portion of Soul discernd by the five Senses, the chief inlets of Soul in this age.

2. Energy is the only life and is from the Body and Reason is the bound or outward circumference of Energy.

3. Energy is Eternal Delight. (Plate 4, Erdman 34)

Unlike eternal torment inflicted on the sinful in Dante and Milton’s hell, Blake sees the infernal not as a thing in itself, but as something only comprehensible and sensible when directly contrasted with heaven. Hell allows humanities’ energies (Blake’s term for our desires and thoughts) to roam unrepressed and create new possibilities, whereas the order, regularity, and structure of heaven restrain these creative possibilities. Not that Blake worshipped the Devil above God but rather that any concept of God without the balancing presence of the Devil represented no true understanding of divinity.

Christianity following the neo-Platonic tradition declared the flesh (σάρξ, σαρκός), the mortal coil, the enemy that leads the spirit (πνεῦμα) into sin. Our mind that can admire the beauty of divine knowledge and creation is trapped in the body’s weakness, its desire for pleasure, sex, money, and power. Yet, for Blake, there could be no separation of body and soul (or mind as we’re wont to call it today). We have simply by convention decided to call Energy (or our carnal desires) “evil” and our Soul or Reason “good.” By taking poetic forms common to religious texts, like the Biblical proverbs, Blake hopes to invert those assumptions and thereby expose them as choices made by humans not as dictates sent by celestial authorities. The “Proverbs of Hell” therefore teach us that:

Prisons are built with stones of Law, Brothels with bricks of Religion. (Plate 8, Erdman 36)

The tygers of wrath are wiser than the horses of religion. (Plate 9, Erdman 37)

These maxims might resonate all too well in the contemporary moment as allegations of widespread sexual abuse of minors among Catholic clergy, endorsements of laws condemning sexual minorities to death from African Anglican leaders, and planes exploded in the name of faith. Institutionalized religion is no less subject to the baser impulses of humanity than political organizations or criminal gangs.

Indeed, for Blake, the danger of organized religions would not even be the harms mentioned above, so much as the dogmatic, orthodox thinking that prevents people from questioning authority and exploring their imaginative potential. Rather than think for ourselves, we rely on another to tell us how to behave, and so the tigers of wrath—an unbridled emotion—seem wiser, or at least truer to our humanity, than the horses of religion, or those animals that force and coercion has domesticated and converted into mere beasts of burden. Institutionalized religions and laws offer only one path for life and blind us, like the bridled horse, to the other ways that diverge from that road.

As Blake wrote in the poem “London”, “the mind-forg’d manacles” constrain civilized human beings from thinking differently, but they are also chains of our own creation. His poetry strives to bring two diametrically opposed positions into stark relief against one another in order to bring the reader to doubt both sides. Only by holding the contradictions in mind simultaneously can we perhaps be freed from our dogma, our well-beaten ruts of thinking and living. Blake’s poetry is therefore simultaneously conventional in its rhyme and meter and yet iconoclastic in its content and imagery. It is like a call to revolution set to the tune of a traditional ballad, instead of dissonant chords.

In this preference for dualisms or contraries, the mythology of his poems can only assimilate the 18th century Enlightenment with difficulty. On the one hand, the European Enlightenment’s call for secularism and rational argument against miracles and other religious dogma support Blake’s trumpet blasts against the walls of organized religion; and on the other, the elevation of rational calculation denies the importance of humanity’s other Energies and sexuality. The scientific measurement of the world threatens to merely project the mind of man onto the external world and therefore foreclose our thinking to other possibilities. The Newtonian view of the universe and Locke’s tablea rasa were particular targets in the epic poem Jersualem

I turn my eyes to the Schools & Universities of Europe

And there behold the Loom of Locke whose Woof rages dire

Washd by the Water-wheels of Newton. Black the cloth

In heavy wreathes folds over every Nation; cruel Works

Of many Wheels I view, wheel without wheel, with cogs tyrannic

Moving by compulsion each other: not as those in Eden: which

Wheel within Wheel in freedom revolve in harmony & peace. (15.14–20, E159)

“Cogs tyrannic” move each other by compulsion, meaning that one event necessarily causes the next in a great chain of causation that stretches from the beginning of time to the end. Philosophers of the period including Newton and Gottfried Leibniz supposed that the universe was a divinely created clockwork in which the cogs all fit together perfectly and drove one another with no need for external intervention. God could simply set the universe in motion and set back to watch his plan unfold, much as a human could wind clockwork and watch it move without any further intervention.

Pierre-Simon Laplace gave the sentiment a more secular gloss in his A Philosophical Essay on Probability published in 1814 when he wrote:

We may regard the present state of the universe as the effect of its past and the cause of its future. An intellect which at a certain moment would know all forces that set nature in motion, and all positions of all items of which nature is composed, if this intellect were also vast enough to submit these data to analysis, it would embrace in a single formula the movements of the greatest bodies of the universe and those of the tiniest atom; for such an intellect nothing would be uncertain and the future just like the past would be present before its eyes. (Laplace, 4)2

Here we have the paradigmatic exposition of the deterministic universe in which the measured position and velocity of every atom can be plugged into a formula to arrive at any future event, which must necessarily be the result of those motions. Such a supposition is of course hubris and pride on the part of our human intellect, and the physics of thermodynamics would reveal that the universe is a far less certain place and liable to decay rather than the perpetual motion that Newton, Leibniz, and Laplace supposed. The computational machines of the twentieth century would open the sciences of nonlinear systems that we commonly call Chaos Theory. Perhaps as Blake would have liked, the universe has turned out to be far less predictable and rational than Newton or even Einstein hoped.

James J. Pulizzi writes about higher education, science fiction, artificial intelligence, and more generally about the collision of science, technology, and media. He earned his PhD from UCLA and blogs at Fractal Realism. Follow him on Twitter: @jjpulizzi

References

- Erdman, David V. ed. The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake. New York: Anchor Books, 1988.

- Laplace, Pierre-Simon. A Philosophical Essay on Probability. Translated by Truscott, F. W. & Emory, F. L. 2007 [1902]., translated from the French 6th ed. (1840).

- See Crabb Robinson’s Diary, Reminiscences and Correspondence (281) for the original quotation.Also in the Wordsworth entry of A Blake Dictionary: The Ideas and Symbols of William Blake. ↩

- French: «Nous devons donc envisager l’état présent de l’univers, comme l’effet de son état antérieur, et comme la cause de celui qui va suivre. Une intelligence qui, pour un instant donné, connaîtrait toutes les forces dont la nature est animée, et la situation respective des êtres qui la composent, si d’ailleurs elle était assez vaste pour soumettre ces données à l’analyse, embrasserait dans la même formule les mouvemens des plus grands corps de l’univers et ceux du plus léger atome : rien ne serait incertain pour elle, et l’avenir comme le passé, serait présent à ses yeux.» ↩