By Dave Jarecki

Working at an independent bookstore during a quarter-life crisis shortly after 9/11 was as good a part-time job as any I might want. Every employee carried around some grudge against their version of “The Man,” from the former radical/general manager, to the community organizing assistant manager, to all the wanna-be-writers—a group to which I belonged—who slung pages back and forth, griped about rejections, and sneered at a new wave of trust-fund authors with books about their lost years in Prague.

The writers we celebrated were from an earlier generation’s drinking class—the likes of Raymond Carver, John Cheever, Charles Bukowski and other white men with lived-in faces who cleaned themselves up then died somewhat reformed. And while my personal reading list stretched beyond these drunken uncles, the writers I turned to—Don DeLillo, Jonathan Krakauer, Kurt Vonnegut—were still of the American white male variety. Even when I branched out and read writers of color—Ishmael Reed, Amiri Baraka, Charles Johnson—the list was still exclusively male. In fact, I made it through college, earned an English degree, and started working in a bookstore without remotely connecting with the work of a single female writer.

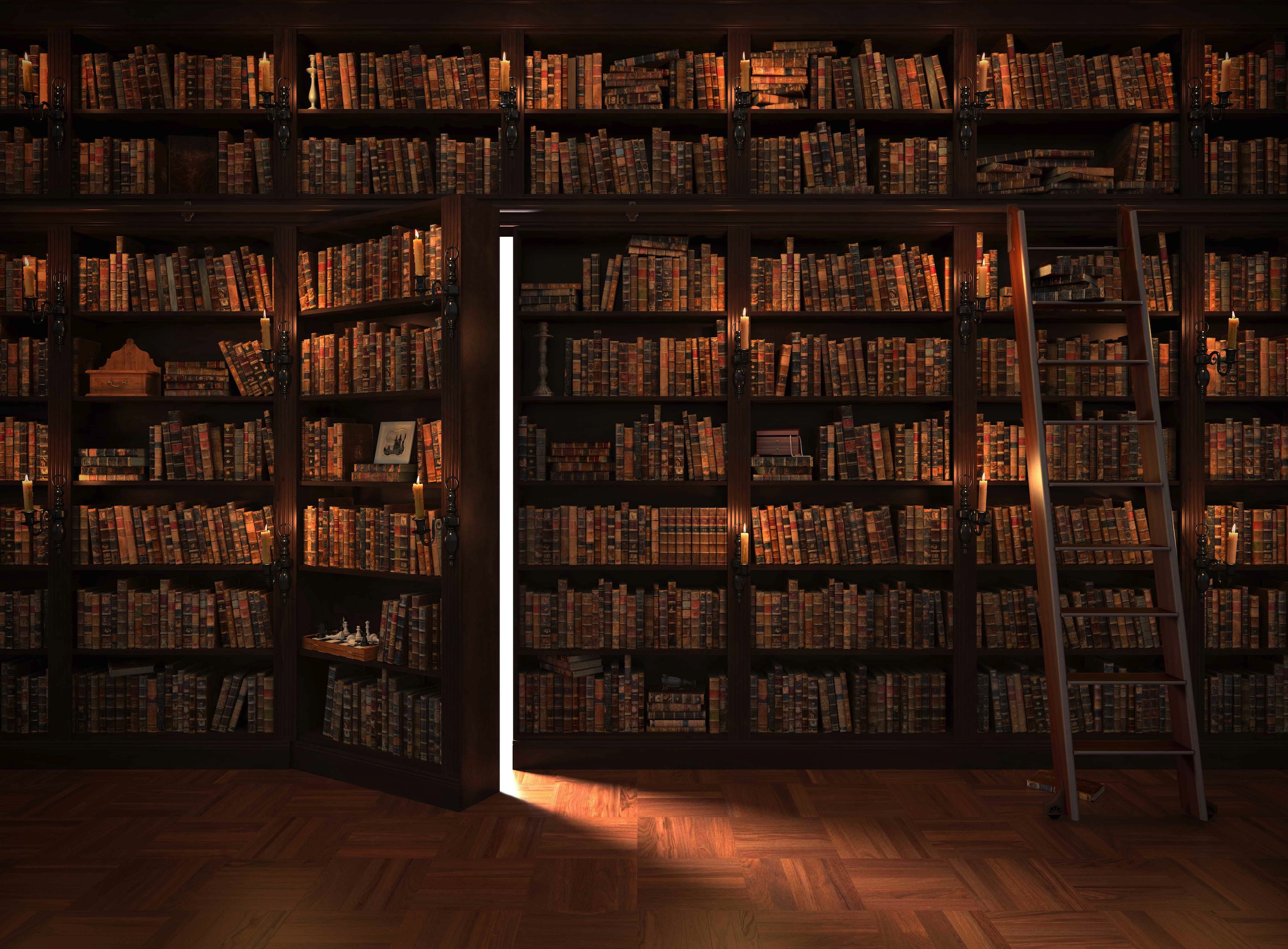

Part of the beauty of working in a bookstore had to do with being around so many titles and genres. This was also a curse. When I squared myself up against everything I hadn’t read, I fell under the weight of a growing sense of self-loathing. I was in the midst of one such episode of critical self-reflection—restocking the biography section, scanning something about Kerouac—when a coworker handed me Savage Beauty, a recently released biography of Edna St. Vincent Millay.

“Have you read it?” he asked.

“No.”

“It’s beautiful,” he said. “And she’s hot,” he added. “Always face this book out.”

I knew exactly one Millay poem—“First Fig,” which I was pretty sure everyone knew, and up to that moment had never seen her face. Some looks simply captivate you in a way you can’t explain or shake. Could be the weight of a stare, an angle of cheek, a dimple. Millay on the cover of Savage Beauty was subtle, a little glib, but certainly someone I found myself wanting to know. I couldn’t stop trying to decipher what she was thinking, like she was onto something and might tell me some of it if I asked her the right way. Before the end of my shift I decided to borrow a copy—another perk of the bookstore—along with a copy of Early Poems from the Penguin Classics Series.

Back at my apartment, my wife, noticing the books, started to ask a question then stopped.

“What is it?” I asked.

“I was going to ask what you’re reading, but then I realized you won’t actually read them.”

“Why?”

“Well,” she said. She picked up Savage Beauty. “It’s too long for you, the author’s a woman, and it’s about a woman.”

As much as I wanted to prove my wife wrong, I couldn’t. Within a week I’d barely cracked the first 20 pages, and hadn’t even bothered with the poems. Two weeks later I’d gotten to page 30. It wasn’t the length of the book, or the author, or Millay. I simply was a terrible reader. I couldn’t sit still long enough to focus on something before my mind spun elsewhere.

I added Savage Beauty to the growing pile of returns I needed to bring back to the bookstore. My own personal “sad pile” as I called it, a tower of borrowed titles that only reminded me of everything I was starting to truly dislike about much about myself or the world around me. Looking at the books sent a time-released drip of angst through me. I didn’t feel good about anything. I kept sniffing around for answers, but if anyone asked what I wanted—career, life, goals, the basics—all I could do was shrug. There was the new war in Afghanistan and the coming war—our invasion of Iraq, still a year away, was already in the wind if you bothered to listen. More personally, I couldn’t find traction in my life. I was 24, had been fired from my first full-time job out of school, and was working two part-time jobs to make things go. And I was headed nowhere as a writer, sure to go straight from wanna-be to never-was.

I put Early Poems on top of my sad pile, made coffee, then picked the collection back up and sat down. The version of Millay’s face that stared back was not the same coy soul on the cover of Savage Beauty. Here she was fierce, her eyelids hooded, her mouth pursed like she’d just finished asking, “What are you gonna do about it?”

Like the terrible reader I was, I skipped the introduction and opened to the collection’s first poem, “Renascence,” without knowing what I was about to fall into.

From the fourth stanza:

I saw and heard, and knew at last

The How and Why of all things, past,

And present, and forevermore.

The Universe, cleft to the core,

Lay open to my probing sense,

That, sickening, I would fain pluck thence

But could not,—nay! but needs must suck

At the great wound, and could not pluck

My lips away till I had drawn

All venom out.—Ah, fearful pawn:

For my omniscience paid I toll

In infinite remorse of soul.

All sin was of my sinning, all

Atoning mine, and mine the gall

Of all regret. Mine was the weight

Of every brooded wrong, the hate

That stood behind each envious thrust,

Mine every greet, mine every lust.

To read “Renascence” was, and still is, an act of submersion. It’s as if Millay gained access to a secret room in the psyche, crept lightly through the door, then reported verbatim through song. I spent half an hour reading it—stopping, staring out the window, closing my eyes, returning to the words. I read out loud. I read quietly. I tracked the cadence, followed her rhythmic changes, studied her willingness to stagger syntax, alter her meter and phrasing. The combined effect is seduction through music, revelation and craft.

My bookstore shift didn’t start until mid-afternoon. By late morning I’d read the poem three times, then swam through as much of Early Poems as I could. I stepped out to our front deck. It was warm for early March in Wisconsin but still cold. I watched my breath twist and float off in wisps. The day possessed a gentle displacement. You could almost see the layers where sadness, joy and calm rested atop one another.

I bounced around from poem to poem, page to page. So many resonated with a meaning that felt as attached to this historical moment as any other. Poems like “Sorrow,” “Ashes of Life,” and “Three Songs of Shattering,” took me back to 9/11 and the days immediately after—falling buildings, a smoldering world. “Indifference,” meanwhile, felt like the mindset I’d tried to adopt since the attacks. With her first three collections in one volume, I moved around, studied various shifts in her voice and approach. In Second April, the last of the book’s three collections, I found Millay to be completely at peace with the darkness she’d dipped in and out of in the first two volumes.

Take “Lament,” a poem where the speaker, dealing with a great loss, is completely certain of herself—even in her uncertainty. The irony found peppered throughout her younger poems is gone, replaced by a dogged-yet-weary determination:

Lament

Listen, children:

Your father is dead.

From his old coats

I’ll make you little jackets;

I’ll make you little trousers

From his old pants.

There’ll be in his pockets

Things he used to put there,

Keys and pennies

Covered with tobacco;

Dan shall have the pennies

To save in his bank;

Anne shall have the keys

To make a pretty noise with.

Life must go on,

And the dead be forgotten;

Life must go on,

Though good men die;

Anne, eat your breakfast;

Dan, take your medicine;

Life must go on;

I forget just why.

Life must go on. Millay wrote and published the three volumes in Early Poems at a time of considerable upheaval, from the culmination of World War I through the rise of European Fascism. Eighty years later, early March, 2002, it was easy to guess that whatever was in the air would no doubt linger—maybe a year, maybe much longer. Certain smells never go away, no matter how many wreaths we lay or regimes we change. In New York, they were digging through an area simply called Ground Zero. The dead were still there. We weren’t ready to forget them. Even as we swore life must go on, we wondered why.

Millay opened a door for me that led to nearly every poet I’ve read since I first encountered her work. I bought the borrowed copy, held onto it for some time, then donated it a few years later during a move. I missed having Millay around, and eventually picked up a new copy. Today her poems move me through bundles of time with grace, and offer a glimpse of an earlier, disenchanted version of myself. I still pause at the book’s cover, amazed at the ripples of thought behind her eyes.

—

Dave Jarecki lives in Portland, Oregon, with his wife, daughter and two hounds. He is currently working on a book about high school baseball in the Pacific NW, and will be entering Portland State University’s MFA in Creative Writing (poetry) program in the fall. @davejarecki